Inspiration and Technology

how runVIBe came into beingInspiration & Technology

Written by Deano

I am an IT network and security architect by career and started running late at 40yrs of age, having never been interested in running or athletics previously.

My sporting history was all about Off-road Motorcycles (moto x, hare scrambles, trail riding and Enduro). I had a passion for dirt bikes and the challenge of riding difficult terrain at speed.

An interest in running was sparked with the purchase of a technical sports footwear retail store to support my wife Lisa’s Podiatry business. I had started running regularly to support the stores run group and once the run groups were underway, our Shoe Clinic store manager, an ex-pro triathlete who was still competing regularly, convinced me that triathlon would be a great way to cross-train. This led to a more focused training effort with more running hours logged and my first foray into running technology with heart rate monitors and sport watches acquired.

“It seemed logical that that efficiency must be measurable across all runners”

Following a series of serious accidents previously, a pivotal moment in the switch from machine driven speed to self-created power came when I lost control of my 250cc enduro bike and hit a tree at speed. Time slowed down leading up to the impact and there was the “life flashed before your eyes” moment. I remember thinking that this was it, ‘I won’t get to finish or do all the things I had planned, that I won’t walk away from this’. As things sped up again, a last-minute desperate manoeuvre shifted the impact slightly off centre of the impending tree trunk. Following the bike’s impact with the tree, I flew through the air, missing the tree itself, and landing on my head. Previous crashes had led me to always ride with full protective gear and luckily my neck was protected by a carbon fibre neck brace and with body armour, knee braces, shin guards and boots, I mostly avoided any major harm. Unfortunately I didn’t escape entirely and my arm sustained a compression fracture that went into the wrist joint and left me with a forearm that was shorter by 2cms. Another long stint in plaster followed.

Having spent well over a year of my life either in a cast, brace or splint, and with ongoing pain and niggles I decided it was time to hang up the MX boots and pursue something different. Triathlon looked like the answer. But it wasn’t easy. The first of the running injuries quickly followed.

My first major injury was shin splints (or medial tibial stress syndrome), becoming so bad that stress fractures were suspected putting into doubt any future running.

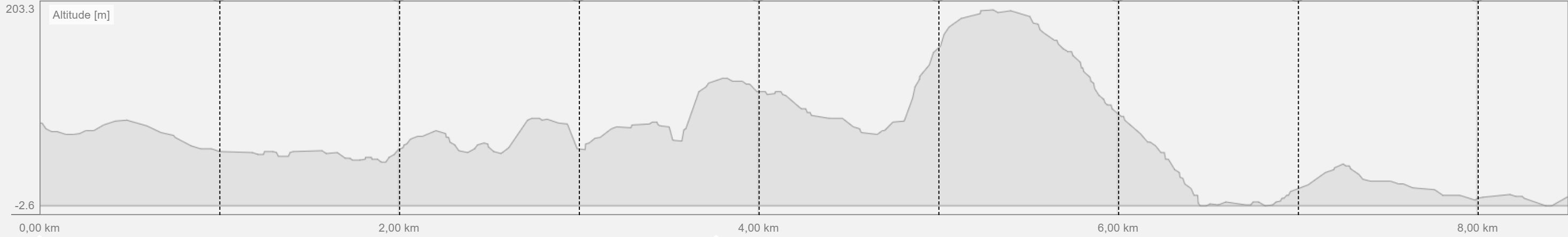

Running the Pukerua Bay to Paekakariki Escarpment Track

Pukerua Bay to Paekakariki – Escarpement Track Elevation Profile

“The research supported this theory but there was no agreed way on measuring it outside of a lab. A metric had not been invented.”

As mentioned earlier I am married to the other half of the runVIBE story, Lisa – a sports Podiatrist with a specialty in sports biomechanics, injury and rehabilitation. Previously I had never paid much attention to Lisa’s world of athletes and their injuries. Now with poor natural lower limb biomechanics, poor running technique, bowlegs and various motocross injuries to bones, joints and ligaments, I was finding I wasn’t the ideal athlete.

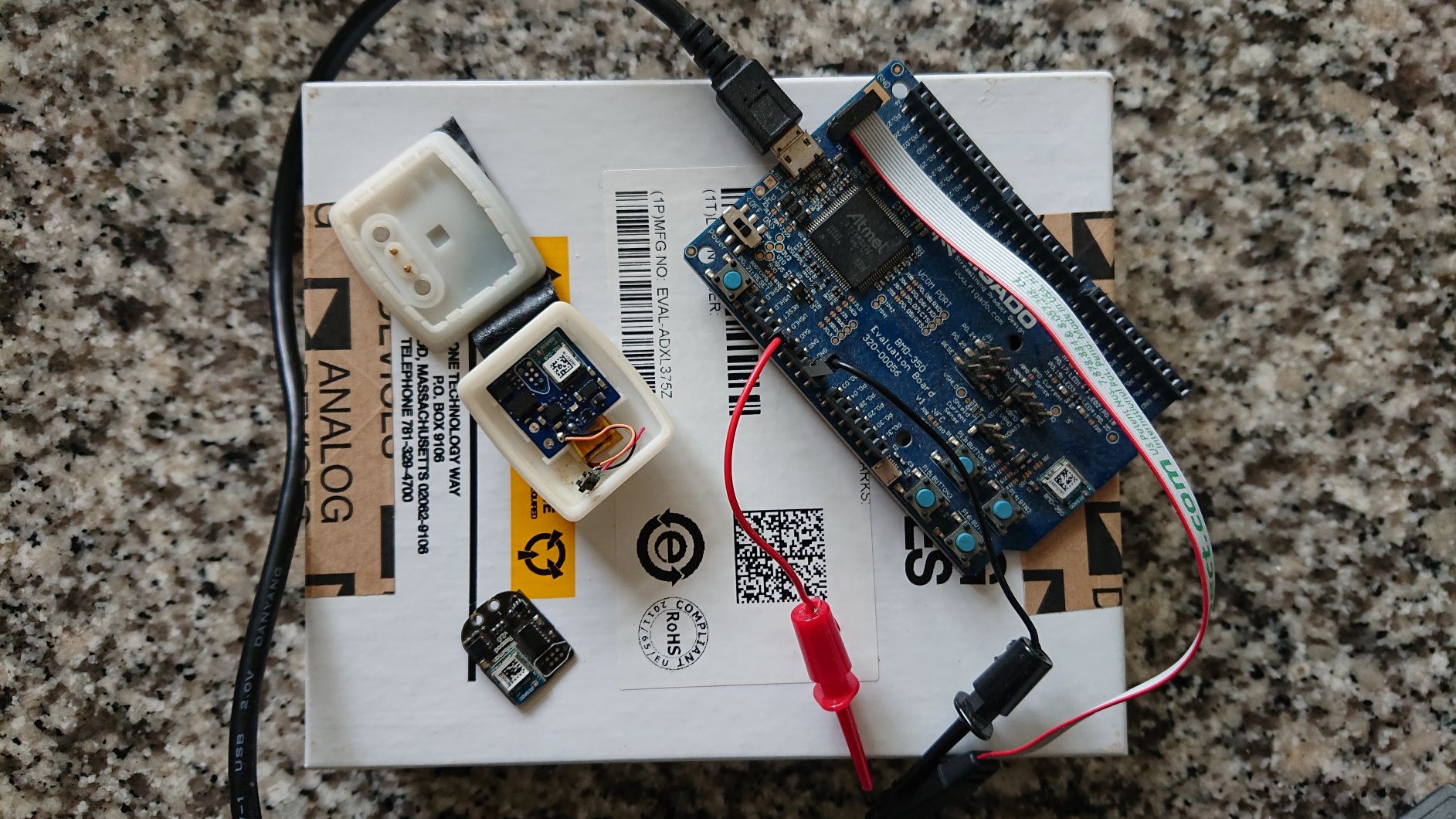

Around this time Lisa was working with accelerometers and researching tibial, ground impact shock with runners and as her research assistant, I had a couple of lightbulb moments.

While collating Lisa’s study results, I was inspired by the athlete sensor waveforms, which showed that people had a unique, individual running signature. We had both previously worked on research about maximising a cyclist’s power delivery to the pedal by changing foot function and these two pieces of research inspired the possibility of an algorithm that would help runners to be efficient, meet their potential and be injury free.

Lightbulb moment 1- different runners exhibited different tibial ground shock waveforms. Could these signatures be used to get runners to run with less impacts and reduce the risk of injury.

Lightbulb moment 2- while studying the raw waveforms from a shock sensor I thought, ’Why can’t we translate the runner’s signature into a power value, from a running efficiency perspective, as is done with traditional cycle power meters?’

Lots of research supported these ideas but no one was offering a running solution as we now envisaged, with a running efficiency metric, directly related to the power expended by the runner.

“I wanted something that would help me achieve my full potential as a runner by helping me to maximise my own running technique, and this was the driving force behind the invention”

“I was interested in what made someone an efficient runner and to find a simple, real-time and relevant solution that enabled you to measure your efficiency and modify your techniques and other factors to improve your results.”

“It seemed logical that that efficiency must be measurable across all runners”

“The research suggested that an efficient runner would be someone who had lower impact forces. It seemed that any energy wasted in impact forces was slowing you down and that this is one of the greatest contributors to being less running efficient.”

“The research supported this theory but there was no agreed way on measuring it outside of a lab. A metric had not been invented.”

Having an expert biomechanist at home meant I had running technique advice able on tap. Lisa could have me tweak my cadence, foot strike, loading rate, impact, foot position, arm swing, posture or whatever, and my injury niggles would go away.

I thought, “what if everyone could have a specialist at home in a sensor that fed them information to manage their running load and form.”

After much discussion, testing and a year of research and study, we developed an algorithm that took the key ingredients of running efficiency and enabled it to be calculated and transmitted to a standard sports watch or smart app as a power value from a small wearable sensor.

After we developed an initial prototype for testing, I logged many hours of running with the sensor. With the output from the sensor I was able to see what happened when I used an inefficient gait, when I ran using mixing principles of efficient running with my natural form, when I used a heel strike gait, ran mid foot or forefoot and when I ran slow or fast.

It WORKED!! The results from the sensor were what we expected to see based on the research.

It was like having Lisa, my running technique/form coach, along with me on every run.